Another reminder that we've got to get Oregon-ized to put the needs of people ahead of cars. It's a matter of life and death.We’re killing our neighbors with our cars

We are literally killing people with air pollution.

It’s a simple fact that tends to get forgotten in the everyday bustle of our lives. And it’s that bustle itself – specifically, zipping to and fro courtesy the internal-combustion engine – that is proving most difficult for air-pollution regulators to fight.

Photo/Flickr and icewaterdog

These points are brought out nicely in a story by Keith Matheny that ran Sunday in The Desert Sun, the newspaper in Palm Springs, Calif. Thousands of people die from air pollution each year there in the Coachella Valley alone.Now, it’s true that Palm Springs is cursed with unfortunate geography of being just over a low pass from Los Angeles, and located in a bowl of a valley. So the gunk in the air from LA and western Riverside County becomes a problem for Palm Springs.

But it’s also true that you could find many places in this country where air pollution peaks to levels considered too high for breathing. Matheny explains:

It’s the mobile pollution sources — diesel trucks, construction equipment, cars, trains and planes — that pose the biggest air quality challenges.

He goes on to point out, though, that the California Air Resources Board has just 50 inspectors to target a state’s worth of vehicles. . . .

Monday, July 13, 2009

We're killing each other with cars

McNary Field: Home of the Salem Cargo Cult

The airport is currently a tax drain on the city and occupies good, centrally located and well drained land that gets plenty of sun (and, yes, rain) -- perfect for a group of investors to take over, continue to run as an private, civil aviation airport if desired and, more importantly, to start using all that safety-buffer space as farmland as well.

Because the airline industry is cratering. The sooner Salem admits that there will never be scheduled commercial service to Salem again, the sooner the airport can be privatized and put on the tax rolls to become a tax generator instead of a tax drain.

Between the price of jet fuel (kerosene, from oil) and the onset of prices on carbon emissions, the bottom line is that that air travel --- one of the most energy intensive human activities --- is going to be less and less a part of our lives in the years to come and it will certainly never be a mass activity for the middle class, as it was for a while.

Salem's leadership seems to be either unaware or in denial about all of this, but the physical facts on the ground will trump any amount of psychological denial. The only question is how many planes will we attempt to build out of cedar planks before we give up our denial and admit that those years are over:

The most widely known period of cargo cult activity, however, was in the years during and after World War II. First, the Japanese arrived with a great deal of unknown equipment, and later, Allied forces also used the islands in the same way. The vast amounts of war materiel that were airdropped onto these islands during the Pacific campaign between the Allies and the Empire of Japan necessarily meant drastic changes to the lifestyle of the islanders, many of whom had never seen Westerners or Easterners before. Manufactured clothing, medicine, canned food, tents, weapons, and other useful goods arrived in vast quantities to equip soldiers. Some of it was shared with the islanders who were their guides and hosts. With the end of the war, the airbases were abandoned, and cargo was no longer dropped.

In attempts to get cargo to fall by parachute or land in planes or ships again, islanders imitated the same practices they had seen the soldiers, sailors, and airmen use. They carved headphones from wood and wore them while sitting in fabricated control towers. They waved the landing signals while standing on the runways. They lit signal fires and torches to light up runways and lighthouses. The cult members thought that the foreigners had some special connection to the deities and ancestors of the natives, who were the only beings powerful enough to produce such riches.

In a form of sympathetic magic, many built life-size replicas of airplanes out of straw and created new military-style landing strips, hoping to attract more airplanes. Ultimately, although these practices did not bring about the return of the airplanes that brought such marvelous cargo during the war, they did have the effect of eradicating most of the religious practices that had existed prior to the war.

Best editorial in a long while: Paul VanDeVelder

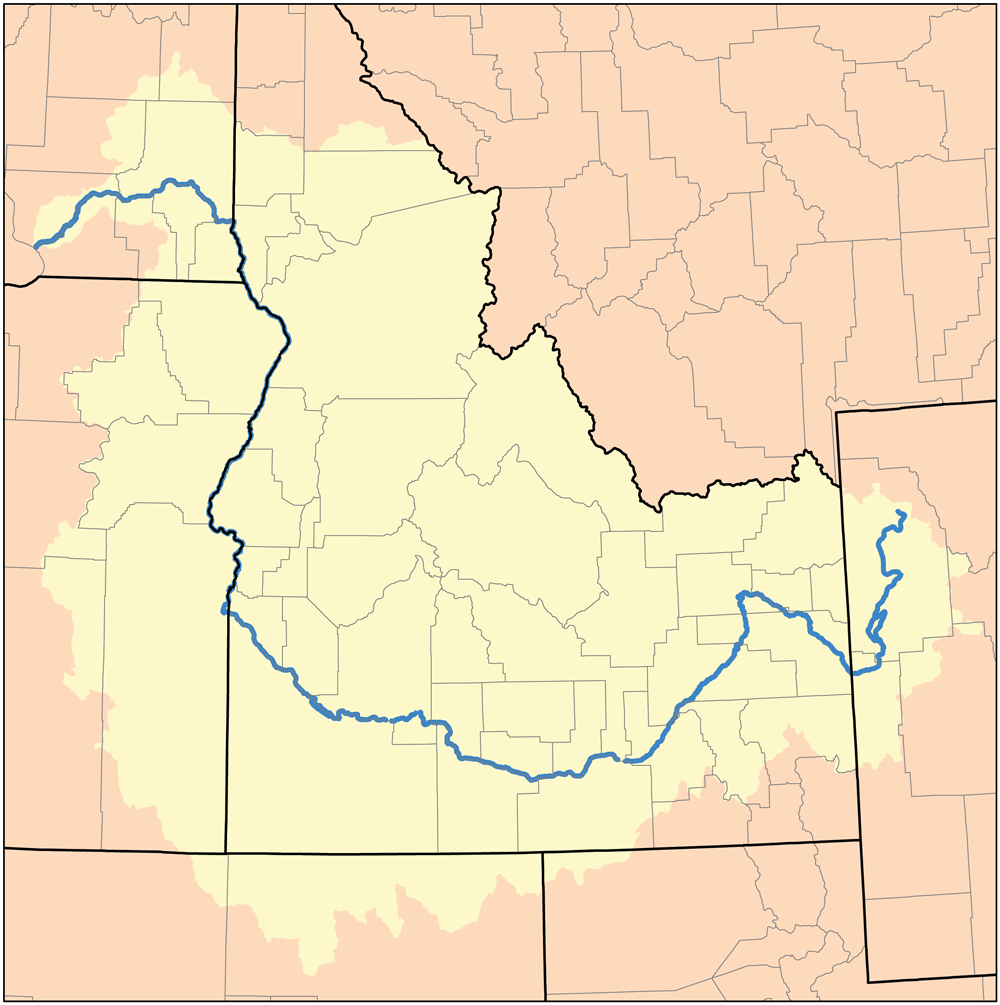

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

If ever there were a story that foreshadowed the political and legal Waterloos that loom in seeking solutions to climate change, surely that cautionary tale is the one about the Columbia and Snake rivers' salmon and their imminent extinction. And like most stories about endangered species or environmental threats, this one is not only about fish and rivers -- it's about us.

The policy deadlock that has resulted from the debate among stakeholders along the Columbia and the Snake -- aluminum smelters, the Bonneville Power Administration, politicians, Indian tribes, states, conservation groups, fishermen, barge operators, agribusiness and wheat farmers -- has flushed billions of taxpayer dollars out to sea over the last 15 years while doing very little to prevent 13 endangered salmon stocks from going extinct. . . .Throughout this stalemate, fish counts have continued to fall, and the underlying science is clear: In river after river where dams have been removed, native fish populations have rebounded and thrived. As the government's former chief aquatic biologist, Don Chapman, concluded, dam removal is the most effective strategy for saving endangered native fish stocks from extinction.

This was the conclusion reached by the Idaho Statesman newspaper back in 1997 after it conducted a yearlong study of the Snake River dams. The paper reported that the economic benefits of a healthy fishery -- and the resultant tens of thousands of jobs -- would swamp the benefits of leaving the dams in place. . . .

If the law and science are unable to trump politics to save this fishery -- a fishery that was the most productive in the world just two generations ago -- how will we ever meet the towering challenges posed by global climate change?

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a223541f-e304-4c95-b1d5-d2c846e73a14)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ad085a72-e9ea-4db6-86b5-8d51632f334d)